How does a fly discover its strategy to that mouldy banana mendacity hid in a kitchen cabinet? A query of that order was posed by researchers on the College of Nevada. The reply seemingly provides clues as to how robotic methods could be educated to search out the supply of chemical leaks or odours, as defined in a study revealed within the journal Present Biology.

“We don’t currently have robotic systems to track odour or chemical plumes,” mentioned co-author Professor Floris van Breugel. “We don’t know how to efficiently find the source of a wind-borne chemical. But insects are remarkably good at tracking chemical plumes, and if we really understood how they do it, maybe we could train inexpensive drones to use a similar process to find the source of chemicals and chemical leaks.”

A elementary problem in understanding how bugs observe chemical plumes is that wind and odours can’t be independently manipulated.

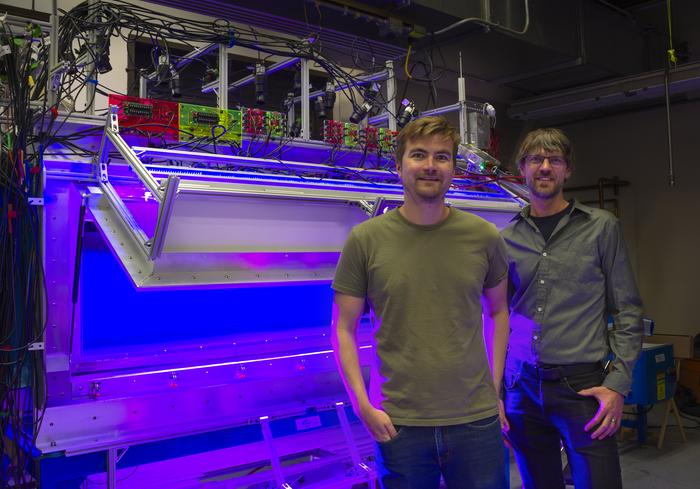

To handle this problem, van Breugel and co-author S. David Stupski used a brand new method that makes it potential to remotely management neurons—particularly these related to scent— on the antennae of flying fruit flies by genetically introducing light-sensitive proteins, an method known as optogenetics. These experiments, a part of a $450,000 challenge funded by the Air Pressure Workplace of Scientific Analysis, made it potential to provide flies an identical digital scent experiences in numerous wind circumstances.

What van Breugel and Stupski needed to know: how do flies discover an odour when there’s no wind to hold it? That is, in spite of everything, probably the wind expertise of a fly on the lookout for a banana in your kitchen. The reply is within the Present Biology article, “Wind Gates Olfaction Driven Search States in Free Flight.” The print model will seem within the Sept. 9 subject.

Flies use environmental cues to detect and reply to air currents and wind course to search out their meals sources, based on van Breugel. Within the presence of wind, these cues set off an computerized “cast and surge” habits, by which the fly surges into the wind after encountering a chemical plume (indicating meals) after which casts — strikes aspect to aspect — when it loses the scent. Solid-and-surge habits lengthy has been understood by scientists however, based on van Breugel, it was essentially unknown how bugs looked for a scent in nonetheless air.

By means of their work, van Breugel and Stupski uncovered one other computerized habits: sink and circle, which entails decreasing altitude and making repetitive, fast turns in a constant course. Flies carry out this innate motion constantly and repetitively, much more so than cast-and-surge habits.

In line with van Breugel, probably the most thrilling facet of this discovery is that it exhibits flying flies are clearly capable of assess the circumstances of the wind—its presence, and course—earlier than deploying a technique that works nicely beneath these circumstances. The truth that they will do that is really fairly stunning—are you able to inform if there’s a light breeze should you stick your head out of the window of a shifting automotive? Flies aren’t simply reacting to an odour with the identical preprogrammed response each time like a easy robotic, they’re responding in context-appropriate method. This data doubtlessly may very well be utilized to coach extra subtle algorithms for scent-detecting drones to search out the supply of chemical leaks.